Each time you see your midwife or doctor in the later part of your pregnancy, they will usually examine your abdomen. One of the main reasons for this is to identify the position of your baby.

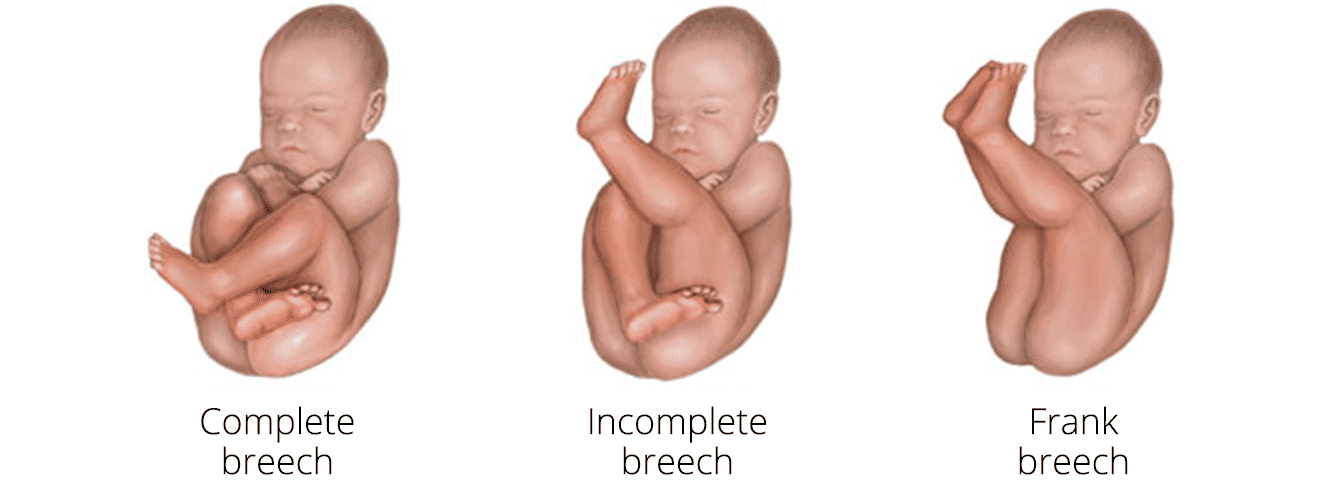

Babies lying with their bottom or feet first in the uterus (womb) instead of in the usual head-first position are called breech babies.

This position is pretty common, but the vast majority of babies will turn around into the head-down position by 36 weeks of pregnancy.

Only 3-4% of babies are breech at the time of delivery, although a suprising 25% arent detected before delivery! This is because examining by hand only identifies 70% of breech babies, and we can be much more effective at picking up babies in this position by ultrasound at 36 weeks. However, due to various reasons, this is not available everywhere!

Statistics for this article taken from RCOG Green top guidelines 20a & 20b

Why is my baby breech?

In the vast majority of situations, it is just chance as to whether your baby turns around. However there are some situations that make breech presentation more likely:

- First pregnancy

- Low-lying placenta (also known as placenta praevia)

- Too much or too little fluid (amniotic fluid) around your baby

- If you are having more than one baby

- Unusual uterus shapes

It may be interesting to know that 10% of subsequent babies also present in the breech position!

Why does it matter?

It is important to be aware in advance if a baby is breech, because it affects options for birth.

There are risks associated with giving birth vaginally if a baby is breech, as it increases the neonatal mortality. These numbers are very small, but is significant. Therefore, if your baby is breech your doctor will want to have a full discussion of your options.

What are my options?

If your baby is breech at 36 weeks of pregnancy, your healthcare professional will discuss the following options with you:

1) Trying to turn your baby in the uterus into the head-first position by external cephalic version (ECV)

2) Planned caesarean section

3) Planned vaginal breech birth.

Can I turn my baby by any other means?

There is no scientific evidence that lying down or sitting in a particular position can help your baby to turn. However, I don’t believe there is any harm in trying, and the website Spinning Babies may have some useful ideas.

There is some evidence that the use of moxibustion (burning a Chinese herb called mugwort) at 33–35 weeks of pregnancy may help your baby to turn into the head-first position, possibly by encouraging your baby’s movements. This should be performed under the direction of a registered

healthcare practitioner.

External cephalic version (ECV)

This is a technique that involves applying gentle but firm pressure on your abdomen to help your baby turn in the uterus to lie head-first. It is successful in around 50% of cases, or 60% if you have had a baby before!

There are some factors that can help your doctor determine if it is likely to be successful for you, such as the weight of the baby, the position of the placenta and the amount of fluid around baby.

ECV is usually performed after 36 – 37 weeks of pregnancy. However, it can be performed right up until the early stages of labour. You do not need to make any preparations for your ECV.

The procedure

The procedure itself begins with monitoring of the baby, and relaxing the muscle of your uterus with medication. This makes it easier to turn your baby.

This medication is given by injection before the ECV. It is safe for both you and your baby. It may make you feel flushed and you may become aware of your heart beating faster than usual but this will only be for a short time.

Before the ECV you will have an ultrasound scan to confirm your baby is breech, and your pulse and blood pressure will be checked.

You will have an ultrasound after the ECV, to see whether your baby has turned.

Your baby’s heart rate will also be monitored before and after the procedure. If you have any bleeding, abdominal pain, contractions or reduced fetal movements after ECV contact the hospital urgently.

ECV can be uncomfortable and occasionally painful but your healthcare professional will stop if you are experiencing pain and the procedure will only last for a few minutes. If your healthcare professional is unsuccessful at their first attempt in turning your baby then, with your consent, they may try again.

After the procedure

If successful, only 3% will revert back to the breech position

Once your baby is turned into the head-first position you are more likely to have a vaginal birth. Successful ECV lowers your chances of requiring a caesarean section and its associated risks.

If your blood type is rhesus D negative, you will be advised to have an anti-D injection after the ECV and to have a blood test.

Any risks?

ECV is generally safe with a very low complication rate. Overall, there does not appear to be an increased risk to your baby from having ECV.

After ECV has been performed, you will normally be able to go home

on the same day.

When you do go into labour, your chances of needing an emergency caesarean section, forceps or vacuum (suction cup) birth is slightly higher than if your baby had always been in a head-down position.

Immediately after ECV, there is a 1 in 200 chance of you needing an emergency caesarean section because of bleeding from the placenta and/or changes in your baby’s heartbeat.

Even if you had one caesarean section before, ECV can usually be carried out.

ECV should not be carried out if:

- You need a caesarean section for other reasons, such as placenta praevia

- Recent vaginal bleeding

- Your waters have broken

- Multiple pregnancy

What if I decline ECV or it is not successful?

It is really important to plan delivery, and you can usually decide between a vaginal breech delivery, or a planned caesarean section which usually takes place around 39 weeks.

The main reason most babies in the UK that are breech are born by C section was as a result of the ‘Term Breech Trial’. This was published in 2000 and analysed 2088 women at 121 centres in 26 countries. The results concluded that planned caesarean section significantly reduced neonatal mortality compared to vaginal breech delivery.

This led to many units completely stopping all vaginal breech births so younger doctors have not had much exposure or training in the techniques required.

Since then, criticism of the trial followed, as there were a number of factors that could have skewed the results, such as that women having planned vaginal deliveries did not necessarily receive electronic fetal monitoring or have a senior obstetrician present.

Therefore the current RCOG guidance advises a discussion of all the risks with a doctor, and either option for delivery can be considered.

Caesarean section is moderately safer for the baby, but has important risks for the mother and potetnial impacts on future pregnancies and births. This leaflet from the RCOG can be useful at understanding all of your options.

Find out more about recovering from a C section here.